[ad_1]

designer491

In the good old days of the 2010s, there was a simple mantra called “risk-on / risk-off.” For most of the time between 2010 and 2020, the switch was set to “on” and money was to be made by placing one’s chips in equities and a handful of other risk assets of various shapes and sizes. Every now and then something happened – Eurozone crisis, China currency devaluation or what have you, and the switch flipped to “off.” For most of us, the off switch was never long enough to merit a deep-seated change to portfolio strategy. This was the heyday, after all, of the “Fed put” – the provision of liquidity (or sometimes nothing more than nice words and assurances) to backstop market risk. If you held a conservative growth-type of portfolio with a decent allocation to quality fixed income securities, that was sufficient to ride out the periodic freak-outs in equity markets.

All That Glitters Is Not Gold, Nor Japanese Yen

For those who wanted to be more creative with their hedging, though, there were a few tried-and-true defensive strategies to be had. Two assets that have long earned regular financial media coverage during risk asset downturns are gold and the Japanese yen, both of which have traditionally been thought of as relatively safe places to be during times of economic turmoil. In the 1970s, for example, an investor with nothing but gold and yen in her portfolio would have outperformed the socks off someone with a traditional 60/40 equity and bond allocation.

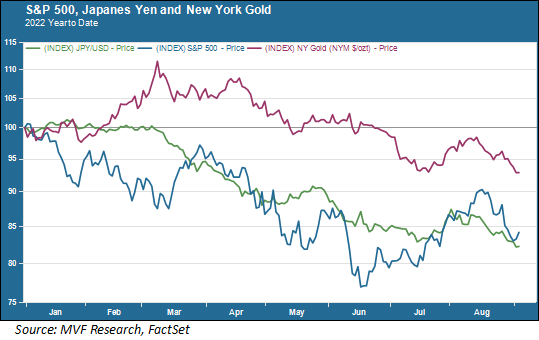

Not so much today. The chart below shows the performance of gold, the yen and the S&P 500 for the current year to date. It does not look very hedge-like.

True – gold did shoot up back in February and March when the stock market went through its first downward cycle of the year. But since then, it has fallen more than 15 percent from the early-March high, which is not what one wants a hedge asset to do. If anything, gold more or less tracked the stock market as the latter lost ground on its way to the mid-June bear market.

The yen has its own story. The chronically low inflationary – and occasionally deflationary – Japanese economy would in theory seem to be an attractive port in a storm while inflation surges elsewhere in the world. But the yen is down more than 21 percent against the US dollar and is trading around a quarter-century low versus the greenback.

The explanation is reasonably straightforward. While the Fed, along with the central banks of most other developed economies, is pursuing a hawkish monetary tightening policy to combat inflation, the Bank of Japan continues to inject massive stimulus into the system through purchases of bonds and equities. Japan faces a number of fairly unique (for now, anyway) economic factors that are formidable obstacles against robust growth and price inflation. As interest rates rise elsewhere in the world, Japanese sovereign debt is still anchored around zero percent (the 10-year JGB yields a quarter percent today, compared to 3.25 percent for US Treasuries and even 1.5 percent for the German Bund, which a year ago carried a negative yield).

Times Change

It’s not just about rates, though. After all, US interest rates rose sharply in the 1970s as well, yet that did not seem to diminish the charms of gold and the yen. But there were other circumstances at play then that are not comparable to conditions today. In fact, the strength of both assets back then can probably be traced directly back to that August day in 1971 when the US went off the gold standard, bringing down the entire edifice of the macroeconomic regime in place since the end of the Second World War.

When the dollar was able to float freely against other currencies, notably the yen and the German mark, pressures that had been building up for years were released, and these currencies soared while the dollar devalued. As for gold itself, its luster grew as a predictable store of value in a volatile climate. Last week in this commentary, we talked about the stop-and-go monetary policy of Fed chair Arthur Burns during the first half of the decade. Interest rates bobbed up and down as Fed policy lurched from fighting inflation to fighting recession, but gold was steady. Even late in the decade, when the more decisive monetary policy of the Volcker Fed pushed interest rates into and beyond the high teens, the price of gold kept going up as investors sought a haven from a world they seemed to understand less and less.

That was then. We have plenty of economic, social and geopolitical challenges today, but they are different in many important ways from the ones of fifty years ago. Times have changed. What worked yesterday does not necessarily work well today, or tomorrow.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

[ad_2]

Image and article originally from seekingalpha.com. Read the original article here.